The Supreme Court recently decided a case on the balance between trademark rights and free speech, especially when parody products are at issue. It has implications for trademark owners and those who wish to skewer them, perhaps for profit.

The case addressed something less lofty: whiskey and dog poop.

What Happened in the Litigation

A company named VIP Products makes a line of dog chew toys called “Silly Squeakers,” which parody famous commercial products. One rubber toy replicates a Jack Daniel’s bottle with a few changes. The bottle bears the brand name “Bad Spaniels” instead of “Jack Daniel’s.” Instead of calling it “Old No. 7,” it used the subtitle “The Old No. 2 on Your Tennessee Carpet.”

Jack Daniel’s Properties, the whiskey maker, was not amused. It demanded that VIP Products stop selling the toy. VIP Products preemptively sued Jack Daniel’s Properties, seeking a declaration that it did nothing wrong. Jack Daniel’s Properties countersued, claiming trademark infringement and dilution of its famous trademark.

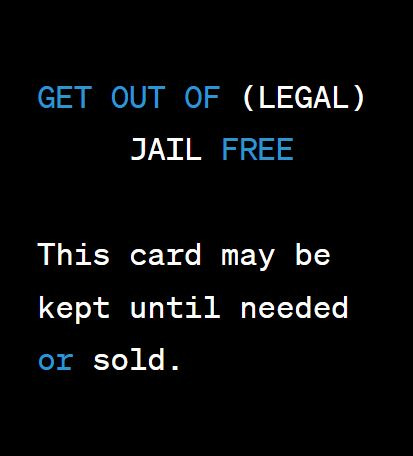

The federal trial court ruled for Jack Daniel’s Properties. In doing so, it refused a request by VIP Products to apply a special doctrine to exonerate it in the case. That doctrine, called the “Rogers test,” is essentially a get-out-of-jail-free card used by people who make expressive works to defeat trademark and dilution claims made against them. After rejecting use of the Rogers test, the trial court held that VIP Products had engaged in trademark infringement and dilution.

VIP Products appealed, and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision. It held the Rogers test applies because Bad Spaniels is an expressive product since it parodies the famous Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle. Using the Rogers test, it exonerated VIP Products.

Eventually, the Supreme Court took the case and decided it this June. The Court held that the get-out-of-jail-free card – the Rogers test – couldn’t shield defendants from trademark-infringement liability when they use an allegedly infringing name as a business, product, or service name, all of which are trademarks.

This doesn’t mean that Jack Daniel’s Properties will win the case. Jack Daniel’s Properties still has to win a trademark infringement or dilution claim to stop Bad Spaniels. That won’t be easy. Here’s why.

Some Background on Relevant Trademark Law

When trademarks conflict with each other, the more recent user has to stop. Trademarks conflict (infringement in legal lingo) when the similarity of the trademarks themselves and associated goods or services is such that a material fraction of the public might be confused as to whether there is a relationship between them, such as being the same company or having a sponsorship, endorsement, or affiliation relationship.

Parody can be a successful defense to a trademark-infringement claim, but it’s tough and expensive to prove parody. A successful parody accomplishes two things: it calls to mind the famous trademark and makes fun of it in such a way that the public will understand that the humor source isn’t the trademark owner. For example, Bad Spaniels would be a legally successful parody if people get the reference to Jack Daniel’s and intuit that Jack Daniel’s didn’t make the toy because there is no way Jack Daniel’s would associate its whiskey with dog poop.

Owners of famous trademarks can stop use of similar names in some circumstances, even when they are used on dissimilar products. This is called dilution. If the attacked use is on something controversial or scandalous, it’s called dilution by tarnishment. For example, this might arise if the mark parody is used for pornography, illegal drugs, tobacco, alcohol, firearms, or gambling.

It’s hard to prove dilution by tarnishment. Few brands are sufficiently famous to qualify for this special treatment. Also, the brand owner has to prove that the unsavory stuff has or is likely to diminish the public’s favorable perception of the famous brand.

The Rogers Test: A Get-Out-of-Jail-Free Card

To complete the picture, here’s how the Rogers test works: It grants artistic works nearly bulletproof protection from trademark infringement and dilution claims.

The doctrine arose from a case concerning a movie called “Ginger and Fred” by the famous director Federico Fellini. The movie depicted a couple of entertainers who made a living imitating Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Fellini made the movie without permission from Ginger Rogers. (Fred Astaire was dead already.) Ginger Rogers sued, claiming the title infringed her trademark rights in her name and her right of publicity, which is the right of an individual to control use of his or her name, image, or likeness for a commercial purpose.

The case developed a legal doctrine that unauthorized artistic usages of trademarks and personas deserve special free speech protection. Specifically, if the unauthorized use of someone else’s trademark (or right of publicity) is for an artistic purpose, it cannot be stopped by trademark law (or right of publicity or dilution law) unless the use has no artistic relevance to the work in which is it used, or, if there is artistic relevance, unless the use explicitly misleads people into thinking there is an association with the referenced person or trademark.

That’s a nearly impossible burden for a trademark owner to carry. Effectively, if the defendant establishes that its work is artistic, it wins.

VIP Products argued it should benefit from the Rogers test because its chew toy (in its view) is a parody, which is a form of expression. The Supreme Court declined to opine on whether the Rogers test is legitimate but held that, regardless, it doesn’t apply whenever the defendant uses as its business, product, or service name (i.e., trademark) the term that is attacked as a trademark infringement or dilution.

Implications for Mark Owners and Parodists

What are the implications of this case?

It strengthens the hand of trademark owners, especially famous trademarks. It effectively takes away the get-out-of-jail-free card – the Rogers test – from the makers of parody products. There might be some room for makers of parody products to claim the benefit of the Rogers test if they handle the branding of their products in a certain way, but that’s a narrow window, and subsequent courts might strike down the Rogers test entirely.

But, as noted above, the trademark owner still has to win the lawsuit under a trademark infringement or dilution theory. Properly done parodies are still legal unless the parody is conveyed through controversial or scandalous things.

On the flip side, people who make parody products must carefully craft their products to make sure the public understands they aren’t related to the skewered famous trademark owner. In fact, beyond parodies, caution and carefulness are now critical in any situation where someone uses or references a popular trademark for a commercial purpose without permission from the trademark owner. Also, because this decision strengthens the position of trademark owners, expect them to be more willing to litigate against unauthorized references they dislike. That’s expensive to defend against.

Implications for Free Speech

And what does this case mean for the state of constitutional protection for free speech? Did the Supreme Court diminish free speech by not applying the Rogers test to protect VIP Products from liability? I think not.

Had this case gone the other way, a trademark-infringement defendant could argue that any riff done on someone else’s mark is somehow artistic expression and effectively exempted by the Rogers test from infringement and dilution liability. That would effectively kill the power of trademark owners to stop infringements in many circumstances, thereby crippling that intellectual property right.

In the past couple of years, the Supreme Court has struck down portions of the federal trademark statute that prohibited the registration of trademarks consisting of derogatory language or dirty words on the basis that the Constitution protects such speech. It thereby enabled the creation of registered trademark rights in such controversial language. Synthesizing those cases with this one shows that the court cares about protecting intellectual property rights and is mindful of free-speech concerns.

And, in this case, the Court did not preemptively ban any speech that criticizes, satirizes, or parodies the trademarks of others. There is no prior restraint. It’s just that if such speech is likely to confuse consumers in a way that constitutes trademark infringement, the party committing those actions may be held financially responsible for that harm and barred from continuing the activity. That’s akin to how the law treats civil torts such as defamation. The law doesn’t try to preemptively prevent such speech from happening, but it gives a remedy for victims harmed by false statements.

As for Bad Spaniels, I think Jack Daniel’s has no interest in burying the hatchet, but it faces a serious parody defense when the case resumes. Speaking of burying, why did the dog bury the whisky bottle in the backyard? Because he thought “on the rocks” meant underground!

Written on July 19, 2023

by John B. Farmer

© 2023 Leading-Edge Law Group, PLC. All rights reserved.